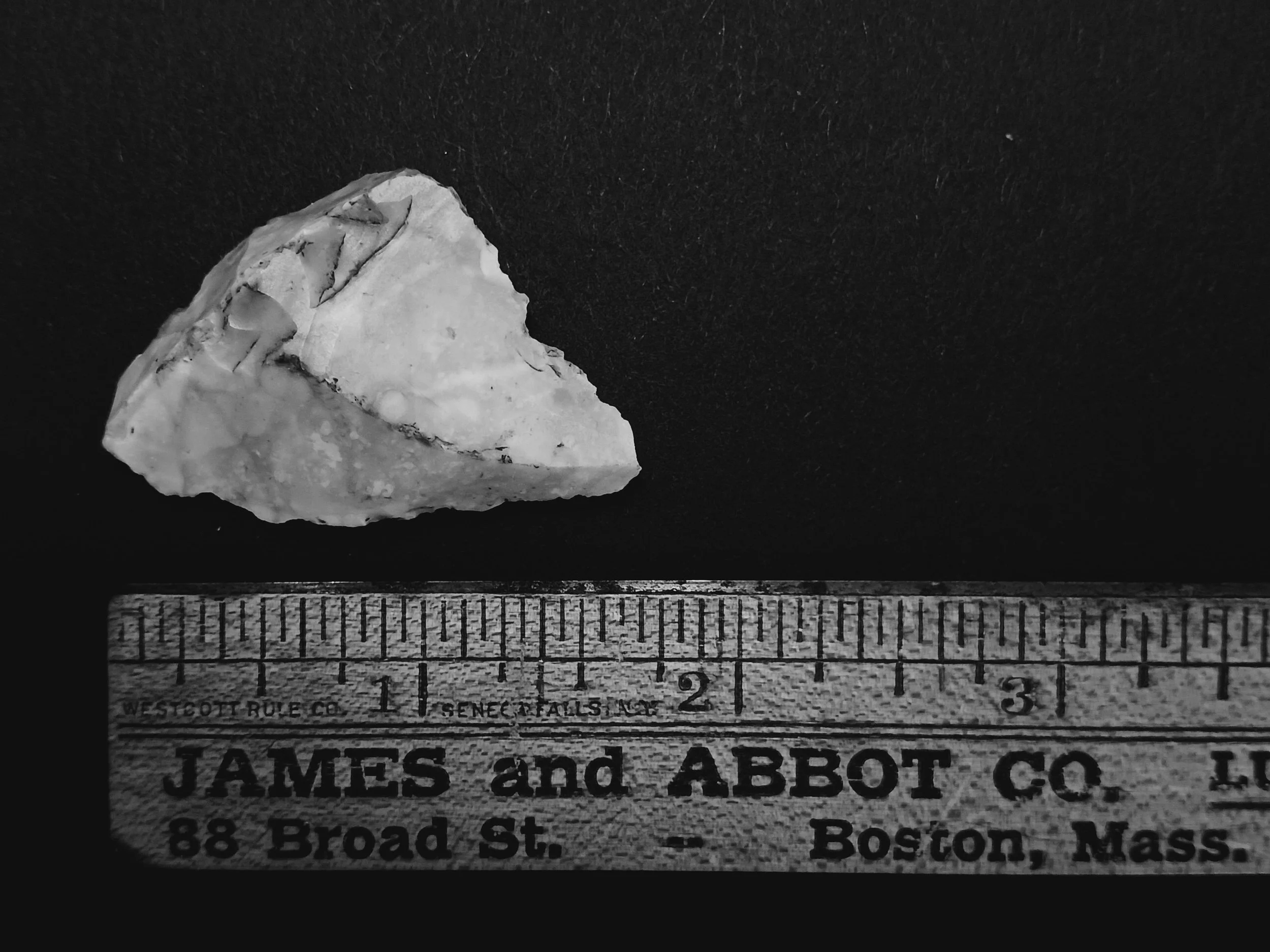

I have a small Neolithic tool on my desk, a triangle of flint, edges carefully knapped, four centimeters at its longest point.

I found it while ‘field walking’ on a Roman site in Norfolk, England, last spring. We were visiting from the States to help my parents get ready to move, my youngest daughter and I, and we also helped walk their dog, Gracie.

The farm fields that were our favorite route had once been the site of a Roman villa, possibly the home of the retired governor of nearby Venta Icenorum. And, from my small flint find, of more ancient inhabitants as well.

Walking Gracie in Norfolk fields

Roman villa, modern farm.

My mother’s friend, Jill, grew up on the farm whose land this was.

“I’ve just ploughed that there field that you like,” Jill’s father-farmer would say when she was a girl in the 1920s. “Go and take a look for those old Roman remains.”

And Jill would scramble over the fresh-turned soil, foraging for a different kind of harvest.

The site was excavated by Oxford Archaeology East in 2014-2015 as part of the Hethersett Pipeline project.

Ongoing pipeline work—still under construction when we visited

It is still a working farm, despite the encroaching bungalows of Hethersett. Ancient buckthorn and craggy oaks line the field edges, silhouetted against the bold Norfolk sky. Each field’s edge has right-of-way for walkers.

Right-of-way for walkers around the edge of every field

The county of Norfolk, in East Anglia, England, is opposite Holland. The two have a similar landscape.

“The glory of Norfolk is the sky,” I tell my daughter as we drink in the beauty of clouds piled as high as Lake District splendor, but more astonishing, being so changeable.

I loved growing up in Norfolk.

English Ladybird—known in Norfolk as a Bishy Barnabee—on a nettle, near the Roman villa

Norwich was not yet designated a UNESCO City of Literature, but I found my niche as a teen regularly attending The Maddermarket Theater, and working an after-school job at The Eastern Daily Press.

The flat landscape of Norfolk did not impede the growth of my imagination or hinder peopling it with the past.

I sailed on Spirit of Boadicea, an ominously named 72-foot ketch run by the charity The Norfolk Boat in conjunction with The Ocean Youth Club, to ports around Europe and in the Cutty Sark Tall Ships Race.

Boadicea/Boudicca, warrior Queen of the Iceni tribe, had sacked Colchester, burned Londinium, slaughtered a Roman legion, and shamed Rome. Founding Venta Icenorum—the ‘market town on the Iceni’—in the heart of Boudicca’s territory was the intriguing Roman response. Overcome them with goods, with intermarrying, with commerce. It worked. And here was the retirement home of the commander, still turning up the material leftovers of that life.

In my childhood, the old Central Library in Norwich—a gift from American airmen, grateful for kindness and welcome during WWII—was the modern-but-flint container of my dreams. Norwich’s chief architect, David Percival, designed the library. He was also responsible for the Sixth Form of The Hewett School, where I attended as a teen.

The Central Library was destroyed in a devastating fire in 1994. Parts of The Hewett School were torn down a few months ago. Neither of these David Percival buildings outlasted my lifetime, but I’m grateful for the design inherent in both. I loved the modern, severe lines of the library, which also incorporated flint, the natural fruit of Norfolk fields.

I hold this Neolithic hand tool and finger its smooth skin, its crinkly, chipped-on-purpose edges. It is utterly manmade, a form of technology, imposed on the face of a clump of flint. It was ancient even when the upstart Romans made their mark on the landscape.

Under a hand lens, you can see the percussion lines where the piece was struck to remove it from the mother node. The reverberation of that, possibly, five-thousand-year-old act is embodied in the stone.

Stone holds its story long. Sailing Spirit of Boadicea, the path we carved through the North Sea settled immediately with the swell. The act of this Neolithic neighbor lives on.

Writing this piece on an Olympia Splendid 33, a German ultraportable typewriter fashioned for the UK market, feels like slipping back in time, a near Neolithic act compared to the swelling tide of AI writing. I am not carving my words in stone, but I am using tools that seem increasingly outdated.

Were there residents of Stone Age Norfolk who clung to the old stone ways as bronze was introduced?

“Oh, Jim, you’re so stuck in your ways. Fancy using stone, still.” Translate to the pre-Celtic, pre-Roman language of which no written words are known.

With mum and Gracie

I was in Norfolk, visiting, to turn over the stones of my childhood and remove all trace of my presence; to finally relieve my parents of the burden of debris, books, paper, school reports(!), horseriding rosettes, and other stuff, most of which should long ago have gone in the rubbish bin. Much of it met that fate now, but the treasure, the markers of moments and corners of my story, I kept. Just enough to fit in our two suitcases, which we’d brought half empty.

Tiles and postcards from the British Museum that we send to my daughter’s Latin teacher

While field walking, we did not turn up a coin or anything of great value. Just this small flint tool, and a tissue-worth of orange, Roman roof tiles—the villa site had its own kiln for firing tiles, and they are still abundant.

And the stuff of my childhood was mostly debris, yet the story was written by their presence. I was glad of the chance to acknowledge their reality, even as I let them go.

Such personal archeology is layered—painful and hopeful in turns.

I unearthed a letter of encouragement from the Hewett School headmaster, Dr. Roy, encouraging me in my writing.

It is typewritten, hand-signed, a physical fact—astonishing. Because it is a letter that I have no recollection of receiving. At sixteen, I sent in an entry to the Whitbread Young Writers’ Award. How this busy headmaster of two thousand students got hold of the entry or had time to read and comment on my novella is beyond me.

What I do remember: the negative words from my otherwise brilliant English teacher, Mrs Elkins, roasting my Whitbread Young Writers’ Award entry.

And above all, I remember the devastating criticism published by the judge for the award, novelist Martin Amis, after the fact, in the national press. Amis lambasted the whole lot of the youthful entries and despaired over the future of writing in England.

The chilling effect of his words was real.

The gracious encouragement of Dr. Roy, layered over with such earth of time, was silent in my memory all these years, completely buried. Astonishing to find it. A realignment of my personal history.

Last year, I came across Peter Elbow’s book, Writing Without Teachers. The book grew out of overcoming his Oxford tutor’s writing criticism so searing that Elbow could write nothing for years, even as he began a PhD at Harvard and later tutored at MIT.

The Oxford tutor who dished out the dirt on Peter Elbow was, it turned out, also the tutor of Martin Amis—a toxic vein of negativity running through the soil of England.

“Controversial remarks from Amis, known in his younger years as the enfant terrible of the British literary world, remain a regular occurrence,” wrote Benedicte Page in The Guardian in 2011.

Peter Elbow dug himself out from the manure heaped on his psyche. The writing center that he established at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, is still going strong. I visited last fall during a college tour with my daughter and nodded with gratitude to the writing master who spoke life.

And here at my typewriter, pouring out freely such clatter of physical words as want to flow, I unearth the thoughts of flint and field, memory and endurance.

I layer over the unhelpful and utterly old, unnecessary words of a bitter Martin Amis. I delve with tools not altogether modern but not quite Neolithic, my own user manual of effective earth moving, grateful for the opportunity to dig in that Norfolk soil.

I appreciate Peter Elbow’s story of resilience inWriting Without Teachers, but even more appreciate its sequel, Writing With Power, a veritable recipe book of help for getting words out and polished.